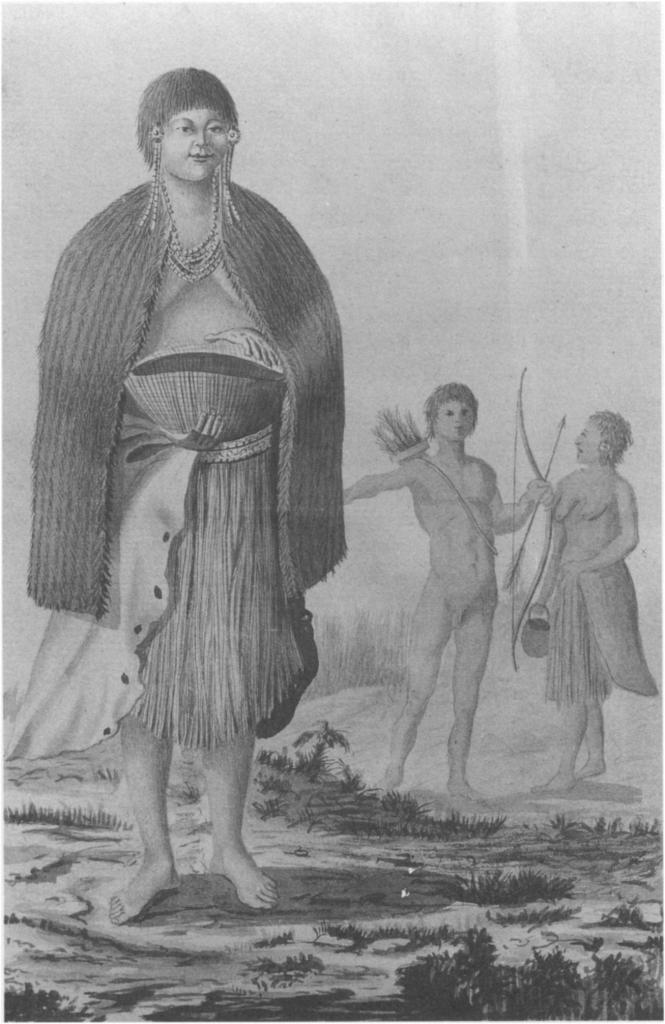

For thousands of years the Native Peoples living here along the central coast of California, the Esselen and the Rumsen (Figure 1), tended the lands with cultural fire and other management practices, creating mosaics of oak forests, redwood forests, savannas, chaparral, and scores of other land and marine ecosystems, which together helped sustain the People, the plants, and the wildlife. Over time, the lowlands and hillsides surrounding Monterey Bay, like in many other places in California, came to be dominated by old-growth oak forests and woodlands, as these provided rich sources of acorns and other important foods.

Figure 1. Native Indians of the Monterey, California area circa 1791 as drawn by José Cardero.

On the evening of December 16, 1602, this all began to change when the first western colonizers, the Spanish Vizcaino Expedition, sailed into Monterey Bay (Figure 2). They were, no doubt, noticed by the nearby Rumsen People, but it wasn’t until the next day that first contact was made. That morning, Ensign Alarcon arrived in a landing boat with orders from the admiral to “make a hut where a mass could be said and to see if there was water, and what the country was like.” He soon reported back that there was fresh water and “a great oak near the shore”, where a hut and arbor were prepared for mass. Upon hearing this news Sebastian Vizcaino and crew embarked to shore and a Catholic mass was said at the improvised altar under this “great oak.”

Figure 2. Vizcaino Expedition of 1602-03.

During their brief two-week visit the Spaniards reported that the Monterey Bay area was “fertile” and dominated by “large oaks and tall pines”. They likewise recorded that there was much wild game and countless species of birds, and that the area was thickly populated by Indians, who were “a gentle and peaceable people” subsisting mainly on seafood and acorns.

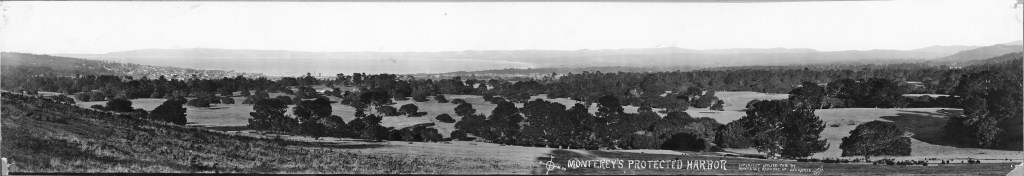

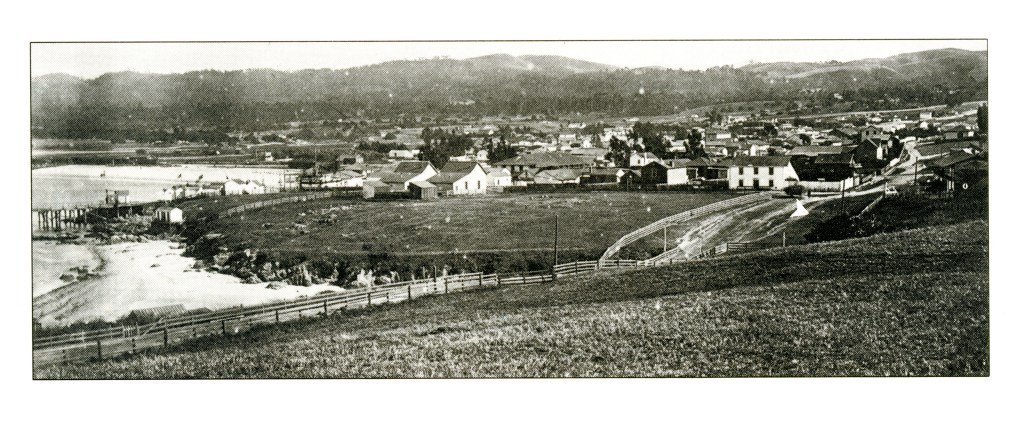

The great oak described by Vizcaino, was notable at the time not only for the size of its canopy but also its easy access from the shore. Thus, it must have been just the first of countless great oaks the expedition encountered on the land. Indeed, an 1839 photo of the landscape just outside the City of Monterey shows extensive tracts of old-growth oak savanna remaining in the area at that time (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Panoramic photo taken in 1839 from Aguajito Rd. showing the landscape on the outskirts of Monterey being dominated by old-growth oak woodlands.

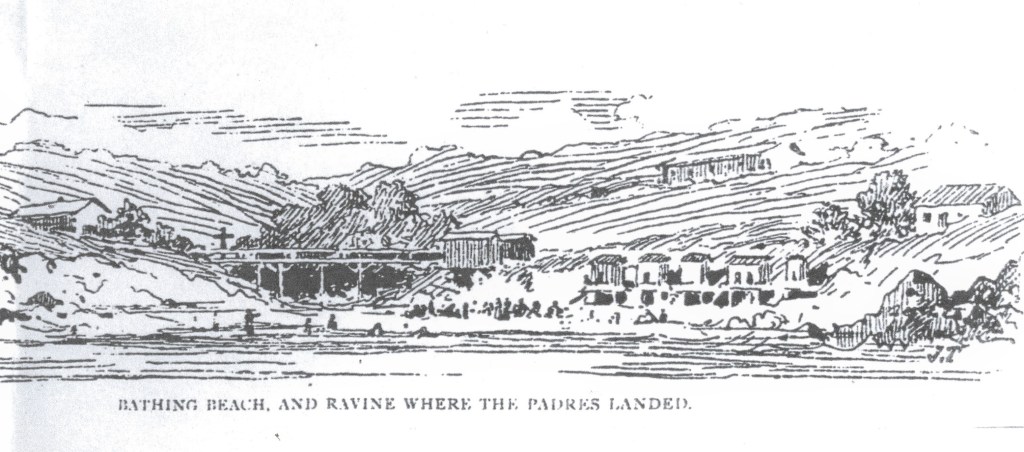

Over a century and a half after Vizcaino’s visit, in June of 1770, Father Junipero Serra arrived at Monterey Bay and reported setting up an altar beneath the same great oak. He then said a mass in commemoration of the first mass of 1602 (Figure 4). And it was eventually recorded that this iconic tree, a coast live oak, lived until 1904.

Figure 4. Artistic composition of Father Junipero Serra celebrating mass in 1770 at a make-shift altar beneath the Vizcaino Oak, by Léon Trousset, 1877.

This great oak, a landmark of first contact, has been called “California’s Plymouth Rock”, and is now mostly referred to as the “Vizcaino Oak”. Given its revered status, there are many records of the life of this iconic tree that reveal verifiable facts which can help answer the often-asked question around here: How old are the largest oaks?

There are several artistic renderings of the Vizcaino Oak that capture its historical significance, including works by Léon Trousset (Figure 4) and Jules Tavernier (Figure 5). Although captivating, these compositions tell us little about the tree’s true size and shape.

Figure 5. Sketch by Jules Tavernier of the Vizcaino landing site from a position on Monterey Bay looking approximately southwest, ca. 1876. Note how Tavernier depicted the Vizcaino Oak (left of center) with prominence and size.

The earliest photographic images of the Vizcaino oak date from the 1870’s and 1880’s. A photo of Vizcaino’s landing site from 1878 captures only the upper part of its canopy, but reveals upon close inspection a fairly dense eastern canopy and an area of apparently leafless branches on the western part of the tree (Figure 6). This observation is consistent with reports that the tree survived a lightning strike in the 1840s which caused severe damage to part of the tree. Another photo from this time shows the upper canopy of the eastern part of the Vizcaino Oak appearing dense and healthy, although the western part of the tree is obscured (Figure 7).

Figure 6. An 1878 photo looking eastward towards the Vizcaino landing site. The upper canopy of the Vizcaino Oak is marked with a small white arrow.

Figure 7. Photo of the Vizcaino Oak canopy ca. 1880 looking eastward. The visible portions of the canopy appear healthy.

There are two historical photos taken from similar locations that show the entire tree, one photo reportedly from circa 1870 (Figure 8) and another reportedly from circa 1895 (Figure 9). The circa 1870 photo indicates the oak possessed a low spreading canopy on its eastern side which appears to be relatively dense and healthy, while the western portion of the oak shows notable damage, presumably from the 1840s lightning strike. The circa 1895 photo also depicts the oak with a relatively healthy eastern canopy, and a damaged western canopy.

However, a close examination of these two photos indicates that they are not chronologically accurate.

Figure 8. Westward view of the Vizcaino oak, reported taken ca. 1870. Note the absence of any large, antler-like branches extending above the main westward (left) branch.

Figure 9. Westward view of the Vizcaino oak taken from a similar angle as the previous photo, reported from ca. 1895. Note the presence of large, antler-like branches extending above the main westward (left) branch, hinting at its former glory.

First, note in both photos the large, damaged branch to the left. In the circa 1895 photo a dead antler-like branch can be seen extending upward from the large, damaged branch. In the circa 1870’s photo, however, this branch is clearly missing, meaning that the circa 1870’s photo was taken AFTER the circa 1895 photo. From this I would simply conclude that these photos, while chronologically inaccurate, are fair representations of the Vizcaino Oak as it appeared on two different occasions in the late 1800’s.

A circa 1880 photo from a different perspective shows the entire oak with a relatively healthy eastern canopy and damaged western canopy (Figure 10). The dead antler-like branches seen in the circa 1895 photo are not apparent here, suggesting again these two images are also out of chronological order. The composite of photos from the late 1800s show increasing leaf and branch density in the damaged part of the tree. Thus, given the state of the canopy, I suspect this photo post-dates both of the previous photos.

Figure 10. A view of the Vizcaino oak reported taken ca. 1880 from a different angle. Note the absence of large, antler-like branches extending above the main westward (right) branch as seen in Figure 9.

In a circa 1900 photo of the Vizcaino Oak, recent excavations are visible in the background that may have led it its ultimate demise (Figure 11). However, the damaged western canopy reveals ongoing recovery of the oak from the previous lightning strike (as in the previous photo) and there are no dead, antler-like branches as seen in the circa 1895 photo. The eastern canopy is somewhat obscured, although the visible portion suggests it was rather healthy. This photo was likely taken within a few years of the tree’s death.

Figure 11. A view of the Vizcaino oak reported taken ca. 1900 looking generally northwest. Note again the absence of large, antler-like branches extending above the main westward (left) branch as is seen in Figure 9. Also note the clusters of other large oaks extending up the drainage (far left).

Weighing all of this photographic evidence it appears to me that, as of the early 1900’s this old oak had plenty of life left in its canopy and could have had a prosperous future. It’s lightning damaged canopy was showing clear signs of on going recovery, and its revered status could have motivated the care it needed to flourish again.

However, in 1904 the Vizcaino Oak died prematurely due to faulty drainage caused by the construction of a nearby railroad.[5] Its remains were then unceremoniously discarded into Monterey Bay.

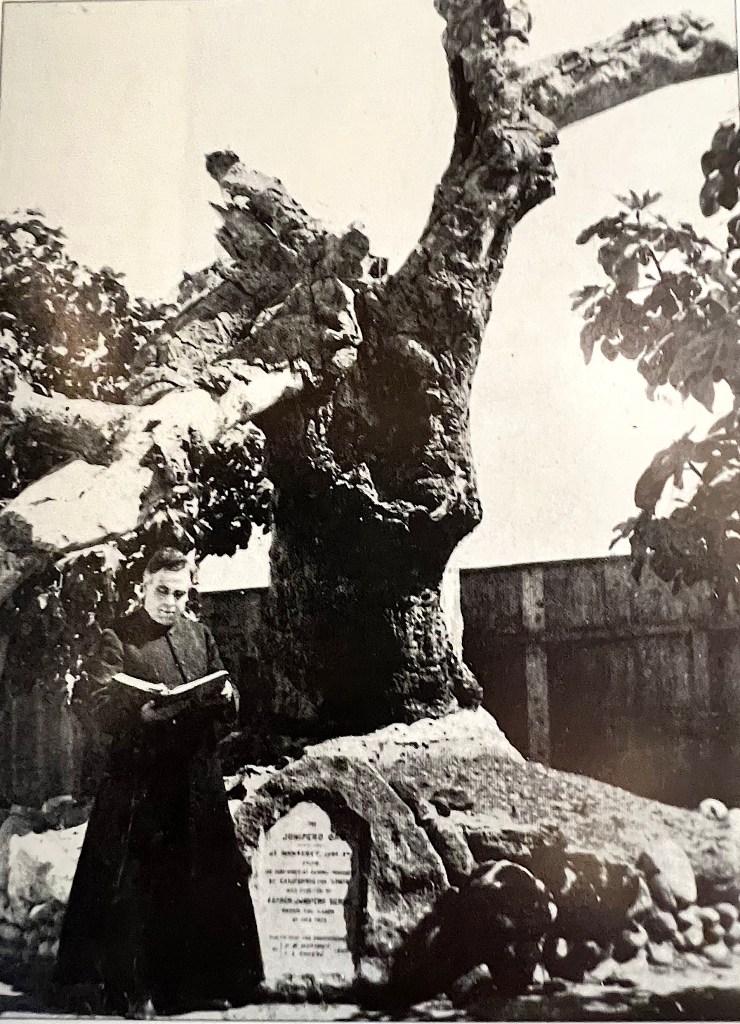

But the legacy of the Vizcaino oak refused to die. In 1905, at the behest of Ramón Mestres, the pastor of the Cathedral of San Carlos Borromeo, its remains were retrieved by local fishermen and brought to the grounds of the cathedral, where the main trunk and lower branches were preserved with crude oil and creosote and the parts which had been eaten away were filled with concrete (Figure 12). The remains of the tree were then erected on a pedestal in the gardens at the rear of the cathedral, where it remained until at least 1987.

Figure 12. The salvaged trunk of the Vizcaino Oak in the garden behind the Carmel Mission in 1905.

The photos from 1905 (FIgure 12) and from 1912 (Figure 13) indicate that this preserved oak had a surprisingly small trunk diameter for such an old tree. Examining Figure 13 closely, there is a wooden fence in the background that can be used for scale. Assuming that the fence is constructed of standard rough-cut 1 x 6” slats and 4 x 4” uprights, I estimate that the diameter of the trunk does not exceed four feet.

Figure 13. The salvaged trunk of the Vizcaino Oak in the garden behind the Carmel Mission in 1912. Note the background fence that is presumably made of 6”-wide slats with a frame of 4”-thick uprights, thus providing a rough measure of the tree’s diameter. Also note the small tree planted at the far right of this photo.

Figure 14. The salvaged trunk of the Vizcaino Oak in the garden behind the Carmel Mission as it appeared in 1987. Also, assuming the smaller, recently-deceased tree on the right (oak?) is the same tree as in the previous photo, that smaller tree would have to have been at least 75 years old at the time of its death.

This account, or epitaph, of the life and death of the Vizcaino Oak provides some fascinating information about the longevity of this oak, which has clear implications for the ages of other large oaks in this region. Let us assume that in 1602 this “giant oak” was no less than two hundred years old, which I believe to be a conservative estimate. This would mean that upon its demise in 1904, it would have been at least five hundred years old, and probably much older. Had this oak not succumbed to the impacts of colonization, who knows, maybe the Vizcaino oak would still be alive today!

And consider, too, that the main trunk of this 500+ years old oak was no more than 4 feet in diameter!

Thus, the tale of the Vizcaino Oak sends a powerful message – that there are tens of thousands of oaks in our region which may be well in excess of 500 years in age. In fact, I would not be surprised to find some oaks that are more than 1000 years old.

I have been studying oaks for more than 30 years and have long suspected that the ages of the largest oaks around here are often underestimated. Below is a photo of a Valparaiso oak, a relative of the coast live oak, located in Big Sur that is nearly 10 feet in diameter and, based on a partial tree core, is estimated to be about 800 years old!

Figure 15. A Valparaiso oak in Big Sur estimated to be about 800 years old! Note how its been culturally modified (i.e. pollarded) long ago by the Esselen Indians (photo by Ben Eichorn).

Most of the above photos were kindly provided with permission by Dennis Copeland of the Monterey Public Library.

For further information and references for the above post, please see “Forged by Fire: The Cultural Tending of Trees and Forests in Big Sur and Beyond” by Lee Klinger https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0D3ZVMB3P

Leave a comment